CONVENTIONAL APPROACH

Solutions-Focused Brief Therapy (SFBT)

SFBT helps clients develop a desired vision of the future wherein the problem is solved, and explore and amplify related client exceptions, strengths, and resources to co-construct a client-specific pathway to making the vision a reality. Thus, each client finds his or her own way to a solution based on his or her emerging definitions of goals, strategies, strengths, and resources. Even in cases where the client comes to use outside resources to create solutions, it is the client who takes the lead in defining the nature of those resources and how they would be useful.

Trepper et al., 2013, p. 3

What is SFBT?

Solutions-Focused Brief Therapy (SFBT) is also known as Solutions-Focused Therapy or Brief Therapy (Healy, 2014, p. 162).

A foundational premise of SFBT is that service users possess the solutions and capacities to “make satisfactory lives for themselves” (de Shazer et al., 1986, p. 207, as cited in Healy, 2014, p. 174). SBFT is a therapeutic intervention that is meant to help service users harness these solutions; it is referred to as a “goal-directed approach” (de Shazer et al., 2007, p. 1), where “goals” are “desired emotions, cognitions, behaviours, and interactions in different…areas of the client’s life” (Solution Focused Brief Therapy Association, 2013, p. 9).

Unlike many psychodynamic practices, SFBT is purely “future-focused” (de Shazer et al., 2007, p. 1) in that it is not interested in revisiting the past or understanding a “truth” (Payne, 2016; Sloos, 2020c). It is also not focused on producing a diagnostic assessment; instead, the service user is positioned as the “assessor” who determines what changes they want to see and how they will accomplish those changes (Solution Focused Brief Therapy Association, 2013, p. 9).

However, unlike problem-solving approaches, SFBT does not spend time identifying or understanding a problem to be overcome; rather, therapy is focused on identifying goals and solutions based on changes that service users can enact in their own lives. Furthermore, SFBT focuses on small wins as opposed to working linearly toward a large goal (Healy, 2014, pp. 175-176).

What are the origins of SFBT?

While it has some roots in systems theory family-based therapies of the 1950s-1960s, the origins of SFBT are often credited to Insoo Berg and Steve de Shazer of the Brief Family Therapy Center in Milwaukee during the 1980s (de Shazer et al., 2007; Lethem, 2002; Healy, 2014).

Berg and de Shazer “began exploring solutions” to research that was taking a problem-oriented approach to family therapy (de Shazer et al., 2007, p. 3). Though it has become a “theory for practice” (Healy, 2014, p. 164), SFBT was therefore “pragmatically developed” rather than arising from a base of theory (de Shazer et al., 2007, p. 1).

What is the role of the social worker within SFBT?

The role of the social worker is to help service users recognize the capacities to enact solutions that they already possess (Healy, 2014, p. 174) and to “expand” the service users’ options (de Shazer et al., 2007, p. 4). While SFBT acknowledges that there is a “hierarchy in the therapeutic arrangement” (p. 3), the therapist-service user relationship is rooted in a “positive, collegial, solution-focused stance” (p. 4) where the practitioner:

believes that the service user has the knowledge and ability to make change in their life and leads “in a gentle way” by “pointing out…different direction[s]” for the service user to “consider” (p. 4);

“almost never pass[es] judgments about their clients, and avoid[s] making any interpretations about the meanings behind their wants, needs, or behaviors” (p. 4);

has an “overall attitude” of being “positive, respectful, and hopeful” (p. 4);

views “resistance” from the service user as either “people’s natural protective mechanisms, or realistic desire to be cautious and go slow” or as a “therapist error, i.e., an intervention that does not fit the client’s situation” (de Shazer et al., 2007, p. 4; Lethem, 2002, p. 190). Resistance is not framed as problematic behaviour; instead, the responsibility lies on the therapist to “discover the ways in which clients are able to cooperate with therapy” (Lethem, 2002, p. 190).

Indeed, the stance of the practitioner, as outlined above, is considered to be one of the key aspects of SFBT.

What are some strengths of SFBT?

There are many components of SBFT that are useful for critical social work practice

Non-pathologizing approach

While SBFT has its origins within ‘psy’ discourses, it has developed into a practice approach that breaks with psychodynamic focuses.

For example, by focusing on solutions as opposed to problems, SFBT avoids pathologizing clients; SFBT does not focus on ‘diagnosing’ service users with biomedical or psychiatric language (Healy, 2014).

As such, SFBT can also assist service users in working toward a solution without placing blame on themselves or others (Lee, 2003, p. 389). This non-pathologizing stance can also make SFBT more accessible to people who encounter internalized or external stigma around mental health support (Lee, 2003, p. 389).

Collaborative approach that centres the service user

SFBT promotes a collaborative approach between service user and practitioner where paths to potential solutions are “co-constructed” by both parties and are rooted in the service users’ goals, language, and perspectives (Solution Focused Brief Therapy Association, 2013, p. 5).

This collaborative approach is in distinct contradiction to the legal and biomedical discourses which position the practitioner as the expert (Healy, 2014, p. 178). Instead, the service user is celebrated as the expert of their own life who has the agency and knowledge to enact change needed.

This also allows practitioners to embrace solutions from “multiple worlds,” including diverse cultural strengths, and “participate in a culturally respectful and responsive therapy process with clients from diverse ethnoracial backgrounds” (Lee, 2003, p. 393).

Illuminates tangible paths forward, via small steps

Unlike “insight-oriented clinical approaches” SFBT is goal-oriented—therapy sessions are focused on identifying actions that the service user can take to achieve what feels like a solution to them (Lee, 2003, p. 390).

However, while SFBT is goal-oriented, goals set within therapeutic sessions do not need to work toward completely resolving a problem; instead, the session aims to identify any steps toward a solution, even if they seem to be small steps.

Therefore, unlike problem-based approaches which often outline a linear path toward “success”, SFBT encourages service users to think of paths toward success in a non-linear approach.

As a result, service users are able to identify concrete steps that inch closer to a place of “solution” without becoming overwhelmed by a needing to complete multiple checkpoints on a specific path toward success.

An Example of a SFBT Practice Approach

Listen, Select, Build

One approach to SFBT is that the therapist and service user can make “new meanings and new possibilities for solutions” through the process of “co-construction” (Solution Focused Brief Therapy Association, 2013, p. 5).

In this process, the therapist focuses on the words that the service user uses to identify some characteristics of a solution, even if small. After the therapist “listens” and “selects” the potential aspect of a solution, and the service user and therapist “build” a “clearer and more detailed version of some aspect of a solution” (p. 5).

In this “listen, select, build” process, the therapist continually raises “solution-focused questions or response[s]” based on the service user’s previous response (p. 5).

Focus on what is observable

Indeed, a key component of SFBT is the dialogue between the practitioner and service user.

Specifically, the “essential therapeutic process” of SFBT looks at what is “observable in communication” (Solution Focused Brief Therapy Association, 2013, p. 4, emphasis in original).

Unlike psychotherapy’s focus on, for example, a service user’s internal thoughts or biological stages, SFBT focuses on what is actually said or done in the “therapist’s and client’s moment-by-moment exchanges” (p. 4).

This means that the therapist has to focus on not “reading between the lines” to try and uncover a “truth” or “underlying meaning” behind a service user’s responses (pp. 5-6).

An important component of the therapeutic dialogue, therefore, is that the therapist actively tries to “listen for and work within the client’s language by staying close to and using the words used by the client” (p. 6).

More ways to apply SFBT to your practice

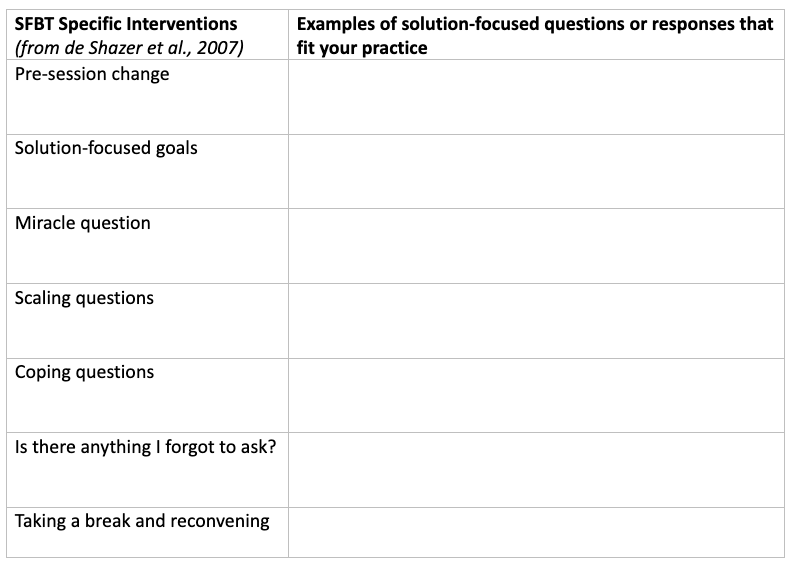

Use the tables below, as well as the information above and resources listed here, to brainstorm some solution-focused questions/responses that would fit within your practice.

However, don’t forget that SFBT has some critical limitations, too.