CONVENTIONAL APPROACH

Narrative Therapy

Origins of Narrative Therapy: A Brief Overview of Postmodern Theories

Narrative therapy aims to explore the narratives of a service user, group, or community, by looking at how these narratives are constructed and how these constructions of identity within the narrative actively shape their experience, sense of self and options (Healy, 2014, p. 218). This focus on constructions of identity stem from postmodern theories which argue that our reality is socially constructed through discourse (or “language practices”) (Healy, 2014, p. 211). Two central theories of postmodernism are postmodern theory and poststructural theory which exhibit “substantial overlap”, however can be differentiated in that poststructuralism studies the relationship between knowledge and language, “whereas postmodernism is a theory of society, culture, and history” (Agger, 1991, p. 112).

Postmodern theories in practice aim to deconstruct and reconstruct “discourses, knowledge, and social relationships” allowing theorists to “question the taken-for-granted or implied assumptions of our thought and knowledge, [analyze] power, and [imagine] new possibilities.” Moffatt, 2019, p. 46

Ken Moffatt (2019) argues that “one should not seek the truth that lies below the surface of relationships and language but instead acknowledge that multiple truths exist because of the wide range of contexts, languages, images, subcultures, and cultures” ( p. 46) A postmodern framework asks social workers to “view all aspects of social work practice, particularly the concepts of client need and social work responses, as socially constructed” (Healy, 2014, p. 205). While postmodern theories will be utilized in this section exclusively to understand and explain narrative therapy, it is important for social workers to familiarize themselves with the basics of these theories, “given that they inform many of the disciplines on which our profession draws” (Healy, 2019, p. 206).

What is narrative therapy?

Based on these understandings from postmodern theories, narrative therapy maintains “that people make meaning in their lives based on the stories they live” (Ricks et al., 2014, p. 100). In other words, the “first person narrative” through which a person defines themself is “based on memories of his or her past life, present life, roles in social and personal settings, and relationships with important others” and, furthermore, the “problems in people’s lives are derived from social, cultural, and political contexts” (p. 100). Much of the leading work on narrative therapy has been developed by workers associated with the Dulwich Centre in Adelaide, Australia. They have produced extensive work on the application of narrative ideas to a broad range of social services work and fields of practice (Healy, 2014, p. 218) which speaks to the far-reach and versatility of this intervention practice.

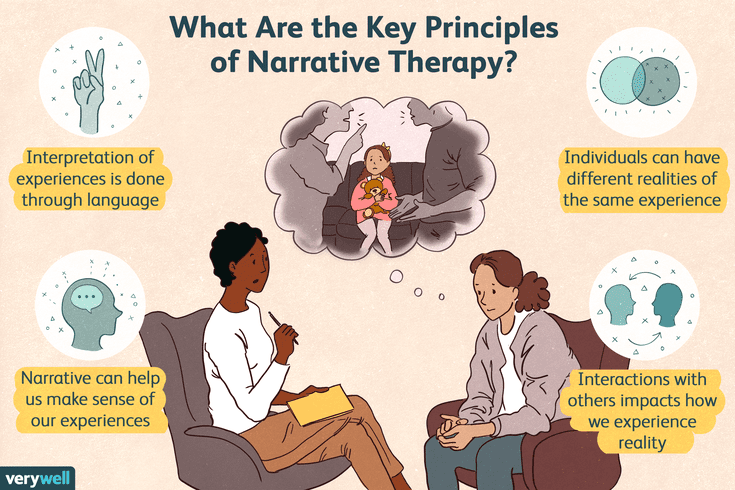

Key Principles of Narrative Therapy.

Image Source: Li, M. (2020) What are the key principles of narrative therapy [Online Image]. Very Well Mind. URL (https://www.verywellmind.com/narrative-therapy-4172956)

The Role of the Social Worker in Narrative Therapy

The purpose of the social worker is to support the individual through the process of identifying the unhelpful narrative as well as to assist with the co-creation and rooting of a second, more helpful narrative.

Narrative therapy can be employed by a social worker when they are engaging with a service user that they believe may be constrained or harmed by narratives they and others have generated about them (Fook, 2002, p. 137). This speaks to narrative therapy’s concern “that the presenting problem is exerting undue influence on shaping the client’s identity” (Dybicz, 2012, p. 268). Healy argues that “because narratives so powerfully shape our ‘identities’ and our life choices, these narratives should be the site of intervention” and ultimately social workers should assist people to “realize new narratives” (2014, p. 218).

Facilitating narrative therapy with a service user requires significant input and skill on behalf of the social worker, relying on particular language and framing of questions to elicit responses that support the service user in deconstructing and reconstructing narratives of self. Dybicz (2012) describes “the client-social worker relationship” in narrative therapy “as that of an author-editor” (p. 281), Ricks et al. (2014) state that “the goal of the counselor in narrative therapy is to help clients develop a new life story that is representative of their lived experiences” (p. 101), and Yuen (2007) explains how she uses narrative therapy to “[render] the skills and knowledges of children and young people more visible and accessible” (p. 7).

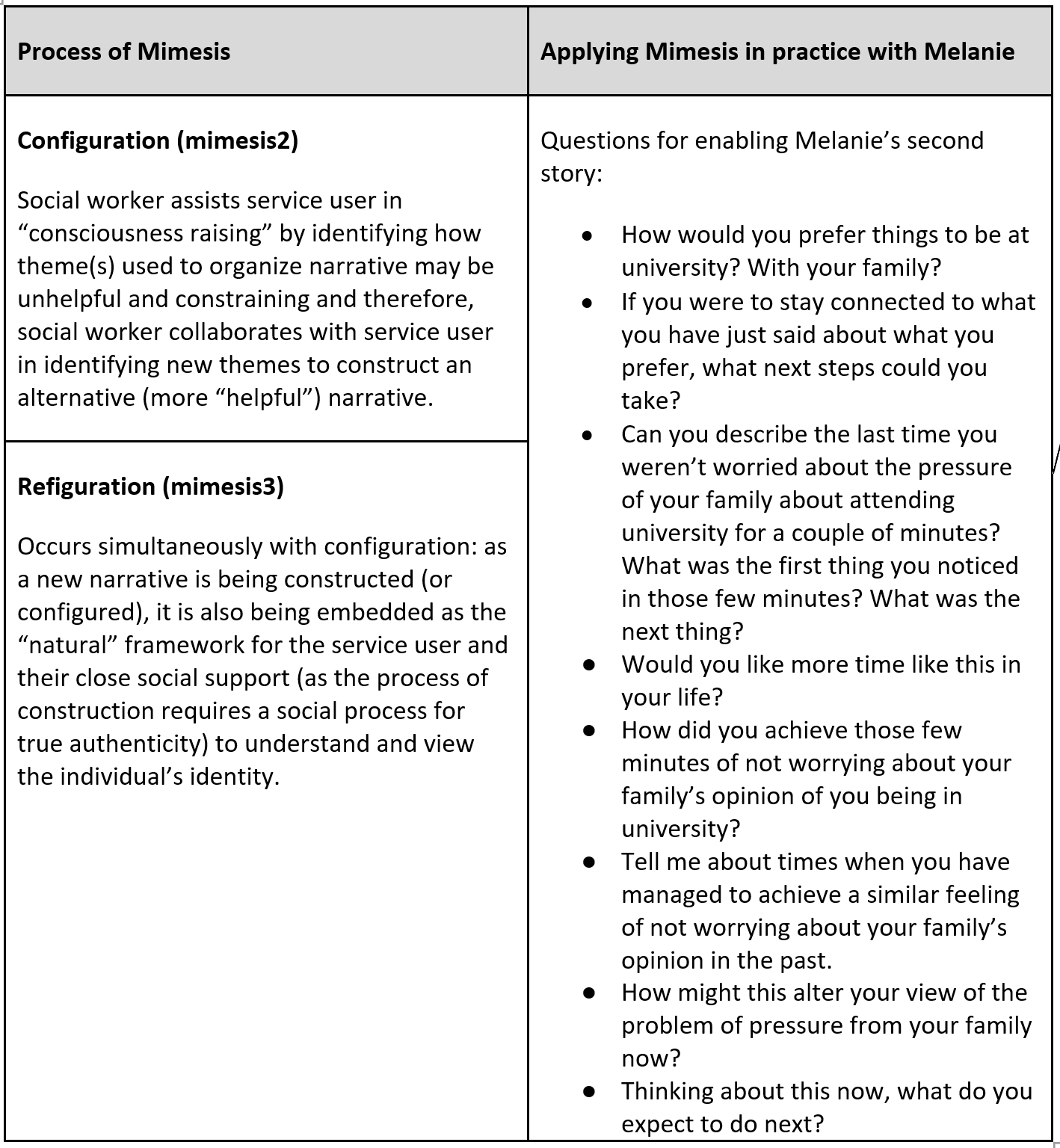

The process of transforming the narrative of self within a narrative therapy intervention is called “mimesis”. Aristotle originally conceived mimesis as “the process of having an image of who we are and who we would like to be, the latter motivating our present actions” (Dybicz, 2012, p. 219). Dybicz (2012) explains that the concept of mimesis was then updated by Riceour “by splitting it into three parts: prefiguration (mimesis1), configuration (mimesis2), and refiguration (mimesis3)” (p. 269). We will practice the process of applying mimesis in narrative therapy in the case study presented below.

The Process of Mimesis.

Image Source: The ontological enrichment of life and story. From "And this story is true..." On the Problem o narrative truth by H. Heikkinen et. al. [Paper presentation]. European Conference on Educational Research, University of Edinburgh, United Kingston. http://www.leeds.ac.uk/educol/documents/00002351.htm

Case Study: Melanie’s Story

Melanie is a cis-female in her mid-20s that comes to her campus counselling services seeking support for feelings of depression, frustration, and resentment. She explains to the counselor that she doesn’t know if she should stay in university and that she feels depressed and frustrated that she doesn’t know what she wants from her life. She states that she has been trying to finish her degree over the last five years but that bouts of depression and anxiety have kept her from doing so. Furthermore, she explains that she doesn’t really like her program and that she’s only in school because she thinks her family will look down on her if she doesn’t get a university degree. She says that her mother and two sisters all have graduate degrees and are very successful and she feels like they think she is dumb in comparison because she hasn’t been able to finish school. She says that she resents her family for putting pressure on her to go to university and how she now feels she has to complete her studies to prove herself to her family and to attain a good job. When asked what she enjoys outside of school, Melanie shares that she has enjoyed volunteering with services for animals as well as being artistic and creative, especially with make up and hair styles.

Practicing Mimesis in Narrative Therapy Using Melanie’s Story

All questions adapted from Muller, K. Externalizing Conversations Handout. Re-Authoring Teaching: Creating a Collaboratory. https://reauthoringteaching.com/pages-not-in-use/externalising-conversations-handout/

All questions adapted from Ackerman, C. (2002). 19 Narrative therapy techniques, interventions + worksheets. Positive Psychology. https://positivepsychology.com/narrative-therapy/

Strengths of Narrative Therapy

Narrative therapy possesses components that can be useful for critical social work practice.

Challenging biomedical and psy- discourses

Narrative therapy critiques medical and psy- discourses’ emphasis on diagnosis by arguing that the narratives produced through diagnosis, or even the discourse of a diagnosis itself, may be harmful to the identity formation of the service user (Dybicz, 2012, p. 268; Healy, 2014, p. 207). Healy (2014) contends that although these diagnoses are meant to “ultimately ‘help’ the person”, they can actually result in the person feeling imprisoned by a narrative that damages and constrains them (p. 218).

Externalizing Problems and Identifying Strengths of Service Users

A social worker often uses narrative therapy to “separate the problem from clients” (Ricks et. al, 2014, p. 100) through externalization of problems, which is “an approach...that encourages persons to objectify and, at times, to personify the problems that they experience as oppressive” (White & Epston, 1990, p. 38). Narrative therapy not only aims to identify how challenges impact a service user’s narrative of their identity, it also intends to intervene in an effort to construct an alternate narrative that portrays strengths and successes and that can provide a new orientation for clients in understanding and even addressing problems (Dybicz, 2012, p. 268).

For example, Angel Yuen (2007) looks at how “discourses of victimhood, which are often present in instances of childhood trauma, can contribute considerably to establishing long-term negative identity conclusions,” (p. 3). Through her work in narrative therapy, Yuen (2007) supports individuals who have experienced childhood trauma by recognizing both the “trauma and effects that this has on the child’s life” as well as the “second story of how the child has responded to these experiences” (p. 6). This dual focus helps establish how children respond in diverse ways to lessen the effects of the trauma and, furthermore, that these responses demonstrate agency, knowledge, and skills that can be helpful to constructing a new narrative (p. 5).

Creative Applications of Narrative Therapy

Narrative therapy can be applied using a variety of creative techniques to “assist clients in reframing ideas, shifting perspectives, externalizing emotions, and deepening their understanding of an experience or an issue” (Ricks et al., 2014, p. 103). In their article, Ricks et al. (2014) provide an extensive overview of how social workers can use “photos, movies, artwork, writing, and music” as “tools for helping clients rewrite their relationship with their problems” (p. 101). For example, they demonstrate how art can help clients “express declarative and nondeclarative memories, which may not be accessible through verbal therapies” (pp. 103-104). It can even assist clients “with self-expression” because it“brings out any hidden aspects of the self” and “helps capture self-portraits” ( pp. 103-104).